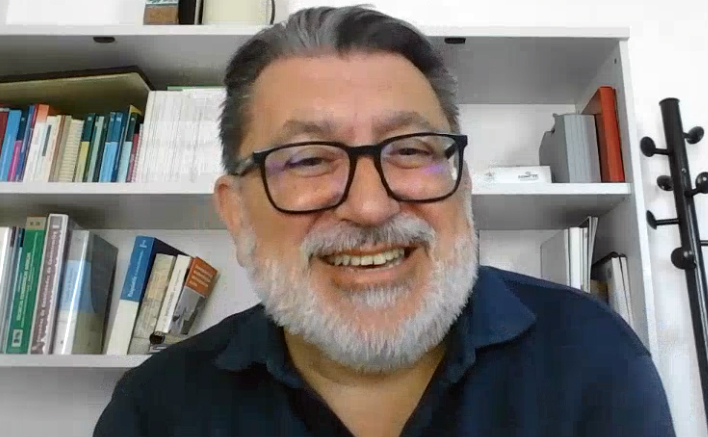

Enric Aragonès took on the role of coordinator of the Tarragona-Reus Research Support Unit (USR) last May, replacing Francisco Martín. He describes this as the “natural evolution,” having started his research career at the USR from the very bottom, as a predoctoral fellow. He has been leading the Mental Health and Primary Care research group at IDIAPJGol for years, a group that includes researchers from both Tarragona-Reus and Barcelona, forming a relatively rare interterritorial collaboration within the Institute.

Aragonès continues his clinical practice two days a week at the CAP in Constantí, something he considers essential to staying connected to reality and being able to ask the kinds of questions that inspire new research projects. He says research brings a critical perspective and helps understand how “it’s often difficult to translate sacred scientific evidence into real life.”

When he takes off his white coat, Aragonès dons a leather apron and retreats to his workshop to sculpt. He is the artist behind the piece “Open Doors to Knowledge”, created for the 25th anniversary of IDIAPJGol. He has an impressive collection of sculptures made of iron and other materials, many of which have been exhibited in group shows.

Aragonès and Josep Basora, Director of IDIAPJGol, besides the sculpture “Doors open to knowledge”

How do you assess your first few months in the position?

I’ve been connected to the USR for over 20 years. I began serious research in 2000, just when the USR and IDIAP were being founded. My entire research career has been closely tied to IDIAP. I’ve been a predoctoral researcher, received project grants and intensification fellowships, and recently, a grant to study abroad. Being the coordinator of the USR was the one thing missing from my journey, and I see it as the natural next step, which makes me very happy.

You received a mobility grant from IDIAPJGol and ICS to visit Chile. What will you be working on there?

I’ll be collaborating with researchers from the University of Talca—psychiatrists and family doctors working on depression management models in primary care. They focus on the role of past trauma in adult depression, which they integrate into regular care. It’s a line of research we haven’t explored, but I think it’s very relevant. I’ll spend a few months learning from them and seeing if we can adapt their model to our own scientific and educational work.

How do you view IDIAPJGol’s overall role in the research landscape?

IDIAP is very valuable for promoting research in Primary Care and quite unique—there’s nothing like it in other Spanish regions.

Do professionals know about IDIAP and that Primary Care research is happening?

IDIAP is well known, although not everyone is interested in doing research. I tell residents and colleagues that you don’t have to be a full-time researcher. For clinicians, doing research is a great complement. We always have open doors. One of my goals as coordinator is to promote this idea and support professionals in turning their research ideas—big or small—into actual projects.

How does research influence your clinical practice as a doctor?

I work in mental health, which is a huge part of family medicine. When I chose my thesis topic, I wanted something connected to my clinical work and underexplored. Mental health was an area I felt less confident in, so I chose it.

Doing research gives you a more critical perspective—it helps you understand clinical guidelines, their evidence, their limits, and why applying them in real life is often hard. If you do research, you understand the gap between evidence and everyday practice, and that critical lens is incredibly helpful.

What are your future goals at the USR?

We’re aiming to secure more international funding, though those calls are complex. We also want to improve internal procedures to help turn clinical questions into research projects.

And how do you see IDIAP’s future?

IDIAP is growing, complexity, functions, and opportunities. As research projects become more complex, we need more technical support. The SIDIAP database is a huge asset, and it will only get stronger. A good goal would be to place IDIAP on the same level as the top hospital research centers. That’s politically and administratively complex but essential for the Institute’s continuity and growth.

How do you view research in the region?

The Tarragona-Reus USR has always been very active and productive in terms of results and implementation. My goal is to maintain that level. We are lucky to have professionals committed to research and management at ICS that values investigation. The idea is to maintain high scientific quality and strong support from leadership.

What makes your unit unique?

We have several strong lines of research. One well-established area is diabetes prevention, which received one of IDIAP’s first international projects. Another is patient safety and quality, led by Montse Gens, a great example of research in action. It has helped develop safety systems and quality assurance in primary care across Catalonia. We also have the respiratory diseases group, led by Paco Martín, which has recently focused on smoking and nutrition, enabling collaboration with Rovira i Virgili University. My group, on mental health, has a long history. A recent development is our fusion with the Barcelona mental health group, which has brought energy, ideas, and resources—making us more effective.

What are you currently working on in the mental health group?

We’ve been working on the MESTRAL project, which started after the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the need to address professionals’ mental health and burnout. The ICS Primary Care launched a program to improve emotional well-being and prevent burnout, with psychoeducational interventions led by community psychologists. At IDIAP, we evaluated the program. We’ve just completed the project, funded by PERIS, and we’re now looking into how the results can improve the intervention and be scaled and extended to other areas.

Can you share any preliminary results?

In terms of effectiveness, the intervention improved professionals’ resilience and reduced burnout scores. Qualitative studies also showed improved team cohesion and recognition of the clinical psychologists’ roles. Primary Care leadership at ICS also viewed the intervention positively.

How long did it last?

The project ran from mid-2022 to the end of 2024. It’s a good example of impactful research. In fact, we’ve submitted it for the “Impactful Research” awards. I’ve always been interested in research that’s practically useful. For instance, the INDI project—focused on improving depression management in Primary Care—started as a clinical trial and later transitioned into implementation. Moving from trial conditions to real-life practice is hard, but the process helped us identify key barriers.

Another project you’re working on is the mental health impact of the pandemic on youth.

Yes, we’re doing that with Constanza Jacques, Ana Lozano, and other researchers, using the powerful SIDIAP database. We’re studying how mental disorders among adolescents and young people have evolved over recent years. The pandemic had a major negative impact, although there was already an upward trend. We found differences based on gender, socioeconomic status, and country of origin. Mental health isn’t just about neurotransmitters—social factors matter a lot. We’re also combining quantitative data with qualitative interviews involving affected youth, teachers, and health professionals to better understand those differences.

When COVID-19 hit, people talked about a mental health pandemic. Are we still facing it?

Among health professionals, the peak impact was during the pandemic and has since eased somewhat. Still, even before COVID, there were unmet emotional needs among professionals. The pandemic made them more visible. Regarding youth, our data goes up to 2022, and we’re now requesting more recent data. But yes, I believe we’re still facing a concerning situation. Once mental health problems emerge, they’re hard to overcome.

ontinuïtat de la institució i continuar amb la seva expansió.